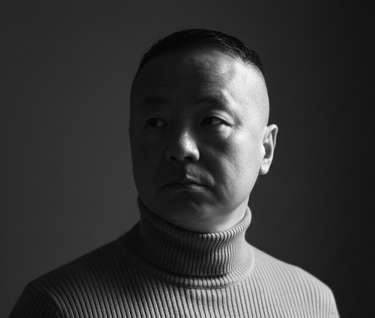

Leo (Liu,Xin) is a contemporary artist based in Prince Edward Island, Canada. His work spans ink painting, oil painting, printmaking, and mixed media, often reflecting climate, place, and lived experience in PEI.

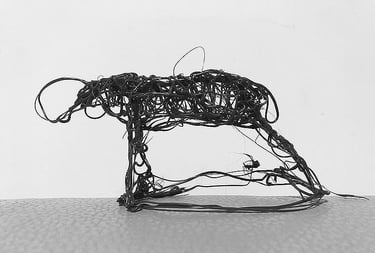

Working across painting, ink, cyanotype, installation, and community-based projects, Xin uses hockey, extreme weather, and traditional East Asian temporal systems as embodied models of conflict and resilience. Rather than treating medium as a stylistic choice, his work operates through expandable conceptual frameworks that connect personal memory with collective experience.

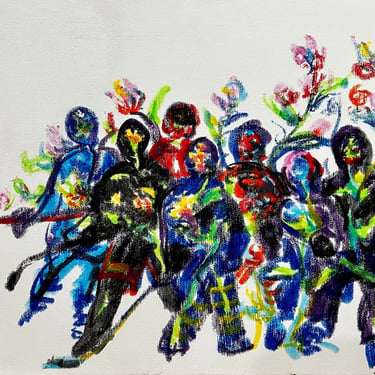

New:Walkflowers!

Catch up on the latest news? Please contact!

Leo (Liu,Xin) has been awarded the Luxembourg Art Prize 2025.

Leo (Liu, Xin)

Portfolio

After many years of academy art, my purpose has become clear: to escape and find the original meaning of life with everything.

My daily routine & my life & what I love.

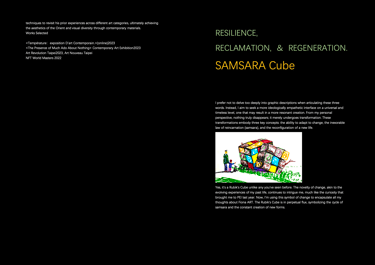

NFT Artwork for All Mankind

An ongoing pixel archive of disappearance.

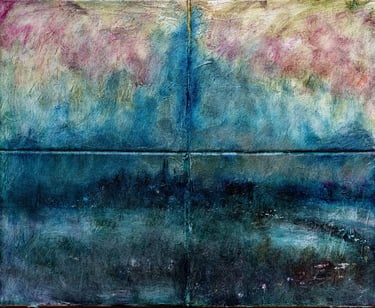

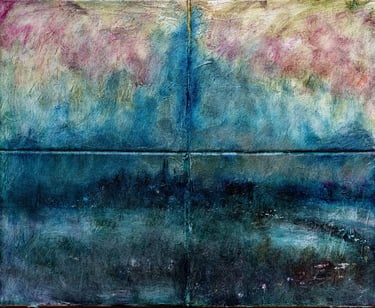

New art experiments in various mixed materials and across categories, is it still art without experimentation?

Join our digital painting workshops and unleash your creativity. Learn the techniques and skills needed to create stunning digital artworks.

My Image Salon

Is food and water and air for all our eyes.

Digital Painting Workshops

Portfolio

Contact

Get in touch with Liu Xin